by Dennis Crouch

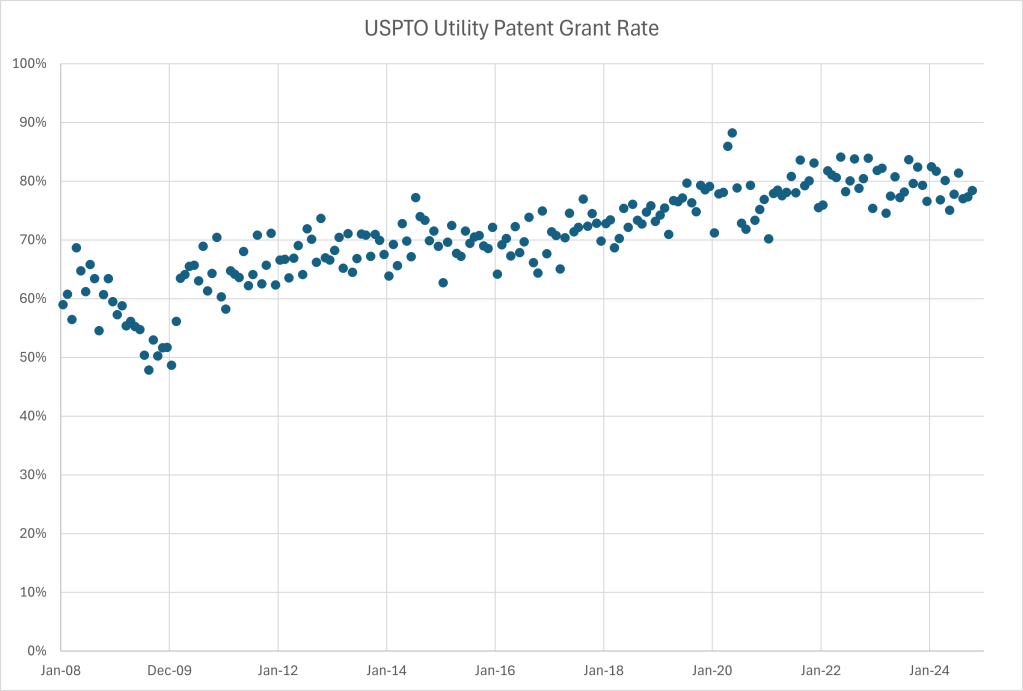

The USPTO utility patent grant rate data reveals an interesting narrative of policy shifts and administrative changes over the past fifteen years. The graph shows a clear upward trajectory from a notable low point around December 2009, when the grant rate bottomed out near 50%, to recent levels hovering around 75-80%. This dramatic shift beginning in 2010 coincided with Director David Kappos taking the helm at the USPTO, marking a decisive break from the more restrictive patent policies of his predecessor Jon Dudas. Under Kappos’s leadership, the office embraced a more applicant-friendly approach, focusing on working with inventors to achieve allowable claims rather than pursuing multiple rounds of rejection.

The USPTO utility patent grant rate data reveals an interesting narrative of policy shifts and administrative changes over the past fifteen years. The graph shows a clear upward trajectory from a notable low point around December 2009, when the grant rate bottomed out near 50%, to recent levels hovering around 75-80%. This dramatic shift beginning in 2010 coincided with Director David Kappos taking the helm at the USPTO, marking a decisive break from the more restrictive patent policies of his predecessor Jon Dudas. Under Kappos’s leadership, the office embraced a more applicant-friendly approach, focusing on working with inventors to achieve allowable claims rather than pursuing multiple rounds of rejection.

More recent data points to subtle but noteworthy changes in USPTO practice. Since Director Kathi Vidal’s confirmation in April 2022, the grant rate has shown a modest decline from its peak levels of around 80-85% during 2020-2021. While the current grant rate remains substantially higher than the pre-Kappos era, this recent downward trend suggests a potential recalibration of examination practices under Vidal’s leadership.

The grant rate shown in the graph represents a monthly calculation derived by dividing the number of issued patents by the total number of resolved patent applications for each month, but with an important limitation: the analysis includes only published patent applications. This restriction is necessary because the USPTO does not publicly release abandonment dates for unpublished applications. Thus, for each month, the rate reflects the number of patents granted divided by the total number of published applications that were either granted or abandoned. While this methodology provides valuable insights into USPTO practices, it notably excludes applications that were maintained as secrets through non-publication requests under 35 U.S.C. § 122(b)(2)(B) and the small number that issued too quickly to be published.

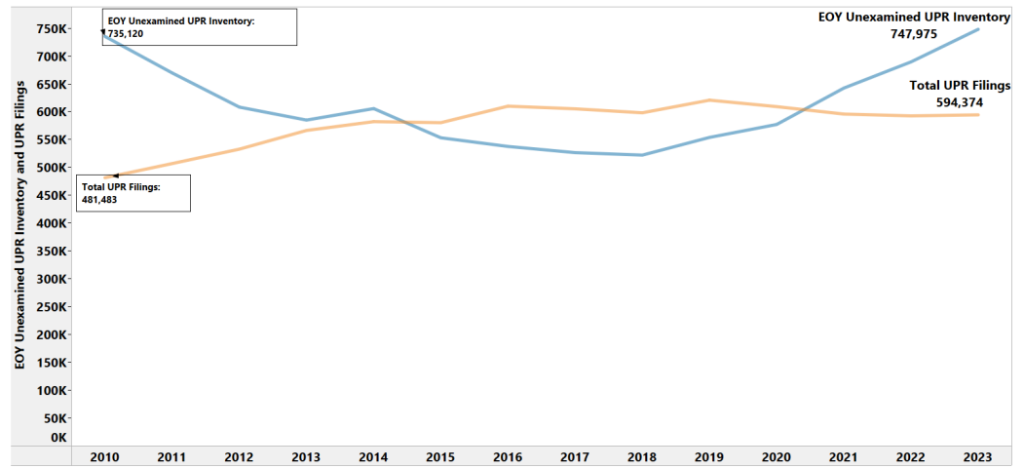

As the allowance rate has slipped, the backlog of unexamined applications has risen sharply in recent years — reaching 804,658 applications in October 2024 which is a concerning increase from approximately 526,000 applications in early 2018. Pendency and backlog issues reached a crisis point in 2008, but we are now above that high point. To be clear, these numbers report what the USPTO calls the “unexamined patent application inventory” which includes applications awaiting a First Office Action by the patent examiner (limited to utility, plant, and reissue (UPR) applications). The backlog of all pending applications also recently reached an all time high at over 1.2 million.

This rising backlog can be attributed to several converging factors: a 2019 reduction in examiner production expectations (i.e., examiners are expected to examine fewer applications than before), increased examiner attrition during the pandemic period (the USPTO is also aggressive about firing patent examiners who are unable to keep up with production), and application filing rates that proved more resilient than initially predicted during pandemic. According to the recent PPAC report, the USPTO is taking a “multifaceted” approach to address the issue – but one that focuses mostly on hiring and training new examiners. Many expect that the presidential a substantial wrench in the gears , many at the office expect an immediate hiring freeze at the beginning of the Trump administration in January 2025. The backlog chart comes from the 2024 PPAC Annual Report.

Backlog Bad or Good?: The USPTO’s examination backlog, often criticized, serves several important functions within the patent system. For many it is a feature rather than a bug. From the Office’s perspective, maintaining a reasonable work-in-progress inventory helps ensure steady employment for its 10,000 patent examiners while avoiding staffing fluctuations that could compromise examination quality — recognizing that hiring and firing of federal employees is quite a chore. Perhaps more importantly, the delay allows for the maturation of prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(2) – the “secret prior art” of competing patent applications that typically become public 18 months after their priority dates. By waiting 12-18 months before issuing first office actions, examiners are able to access to a more complete set of prior art references.

The backlog often aligns with applicants’ interests as well. The examination delay provides breathing room for market development and product refinement, allowing applicants to better understand their invention’s commercial value before having to pay for additional prosecution and maintenance fees. Longer-pending applications tend to undergo more substantial claim amendments as applicants gain market insight and better understand their invention’s scope. For situations where this standard timeline proves problematic, the USPTO offers various acceleration options, albeit typically for an additional fee.

While delayed patent examination offers some benefits to both the USPTO and patent applicants, these institutional advantages come with public costs. First, the extended prosecution timeline often allow time for more dramatic claim amendments that can strategically capture competitor products developed and placed on the market in the intervening years. This practice that might be termed “submarine claiming,” allows applicants to reshape their patent scope in response to marketplace developments, potentially surprising and ensnaring companies who had been operating under the assumption their products were in the clear. At least theoretically, this uncertainty can chill innovation and market entry, as companies become wary of investing in product development without knowing the full scope of pending patent claims.

A second public problem with the long pendency is examination delays typically trigger Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b), which extends patent protection beyond the standard 20-year term. The result is a longer period of market exclusivity and correspondingly higher consumer prices – precisely in cases where prosecution has already been lengthy. This means the public bears a double burden: first enduring the uncertainty of pending applications with evolving claim scope, and then facing extended periods of monopoly pricing due to PTA. The patentee effectively receives additional protection time as compensation for delays that may have already served their strategic interests.

Finally, it is important to recognize that the USPTO’s continued effectiveness depends heavily on maintaining public confidence in the patent system, and excessive examination delays risk eroding that support. A major reason behind President Trump’s election is a lack of public trust in government institutions. And, although the USPTO maintains better than average trust, that support has declined in recent years — and many see the patent system as now serving only the most sophisticated players. Extended pendency periods compound this erosion of confidence because it rewards strategic thinking rather than promoting innovation and clear notice. Even stakeholders not directly harmed by examination delays should consider supporting meaningful backlog reduction efforts in the next administration, as a small but crucial step toward reinforcing public trust in the patent system.