A new lawsuit over Broadway’s Stereophonic tests copyright’s limits, as Fleetwood Mac’s former sound engineer claims the hit play copies his real-life story about working on the Rumours album.

Ken Caillat, the Grammy Award-winning sound engineer and co-producer of Fleetwood Mac’s iconic Rumours album, claims the creators of Stereophonic didn’t exactly go their own way when crafting the hit play. In a newly filed lawsuit against playwright David Adjmi and several prominent Broadway production companies, Caillat alleges that Stereophonic lifts substantial portions of his memoir Making Rumours: The Inside Story of the Classic Fleetwood Mac Album, turning it into a thinly disguised stage adaptation of the book, which chronicles his experiences working on the legendary album.

But despite numerous similarities between Stereophonic and the events described in Making Rumours, Caillat may be looking at a landslide loss. That’s because copyright law poses significant hurdles when it comes to real-life stories, and the line between fact and fiction isn’t always as clear-cut as it may seem.

Thunder Happens

Stereophonic, which tells the story of the chaotic creation of a rock album over the course of a year in the 1970s, has been a huge success. It won five Tony Awards this year, including Best Play, and critics have praised it for its storytelling and emotional depth. They’ve also pointed out the obvious parallels between the unnamed five-member band in the play and famed classic rock group Fleetwood Mac.

In his complaint filed last Tuesday in the Southern District of New York (read it here), Caillat and his co-author Steven Stiefel claim that Stereophonic doesn’t just draw inspiration from Making Rumours—it copies entire scenes, character dynamics, and dialogue directly from their book without permission. The lawsuit alleges that Stereophonic closely mirrors their memoir’s portrayal of the interpersonal tensions and creative struggles behind the making of Rumours, including the depiction of the band’s recording process and the volatile relationships among Fleetwood Mac’s members. The plaintiffs also point to what they say are striking similarities in the composition of the band characters, key scenes they claim are lifted straight from the memoir, and even the set design, which positions the audience in a recording studio, echoing Caillat’s perspective from behind the glass.

The set of Stereophonic, which Caillat claims mirrors the vantage point he described in Making Rumours.

Tell Me Lies

Playwright David Adjmi has insisted in interviews that Stereophonic is his own creation. While acknowledging that the play includes what he calls “superficial details” related to Fleetwood Mac, Adjmi maintains that “any similarities with Ken Caillat’s excellent book are unintentional.” In an interview last month with The New Yorker, he stated, “When writing Stereophonic I drew from multiple sources—including details from my own life—to create a deeply personal work of fiction.”

The plaintiffs say that Adjmi is telling lies—and not the sweet little kind. Yet despite the striking parallels laid out in their complaint, Caillat and Stiefel face an uphill battle in proving their case. That’s because two things can be true at once: Stereophonic may have copied the real-life events described in Making Rumours, but the copying may well not be legally actionable. Indeed—and somewhat ironically—if the plaintiffs succeed in showing that Stereophonicuses characters, events, and dialogue taken directly from their memoir, they’ll face a cold reality: copyright law doesn’t protect underlying facts or interpretations of actual events. And contrary to popular belief, no one needs to acquire “life rights” to tell those stories.

Two things can be true at once: Stereophonic may have copied the real-life events described in Making Rumours, but the copying may well not be legally actionable.

The Chain: Similarities Between Stereophonic and Making Rumours

According to the lawsuit, Stereophonic shares more than just surface-level similarities with Making Rumours. The plaintiffs claim the play mirrors both the narrative arc and key details from their memoir. For example, one of the complaint’s standout allegations involves a scene where a band member assaults the sound engineer during a tense recording session. In Making Rumours, Caillat describes how guitarist Lindsey Buckingham once grabbed him by the neck in frustration. The plaintiffs claim a nearly identical altercation plays out on stage in Stereophonic.

The lawsuit also focuses on the band’s makeup. Just as Making Rumours delves into the personal and romantic tensions between Fleetwood Mac’s members, Stereophonic follows a five-member band—composed of three men and two women—grappling with creative and personal conflicts while working on an album. The plaintiffs point out that the band’s characters in Stereophonic mirror Fleetwood Mac’s real-life members down to their nationalities, and the play is set in a 1970s California recording studio. The character that most resembles Lindsey Buckingham has a brother who’s an Olympic athlete—Buckingham’s own brother was an Olympic medalist. The band’s dynamic even includes two couples struggling to stay together, a clear nod to the turbulent relationships within Fleetwood Mac during the Rumours era.

Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours has sold over 40 million copies worldwide, making it one of the biggest selling albums of all time.

Another key allegation involves the play’s set design, which places the audience inside a recording studio, watching the band’s creative process unfold from the perspective of the sound engineer. Caillat and Stiefel argue that this viewpoint is central to Making Rumours, which gives readers a behind-the-scenes look at the album’s creation from Caillat’s vantage point in the control room.

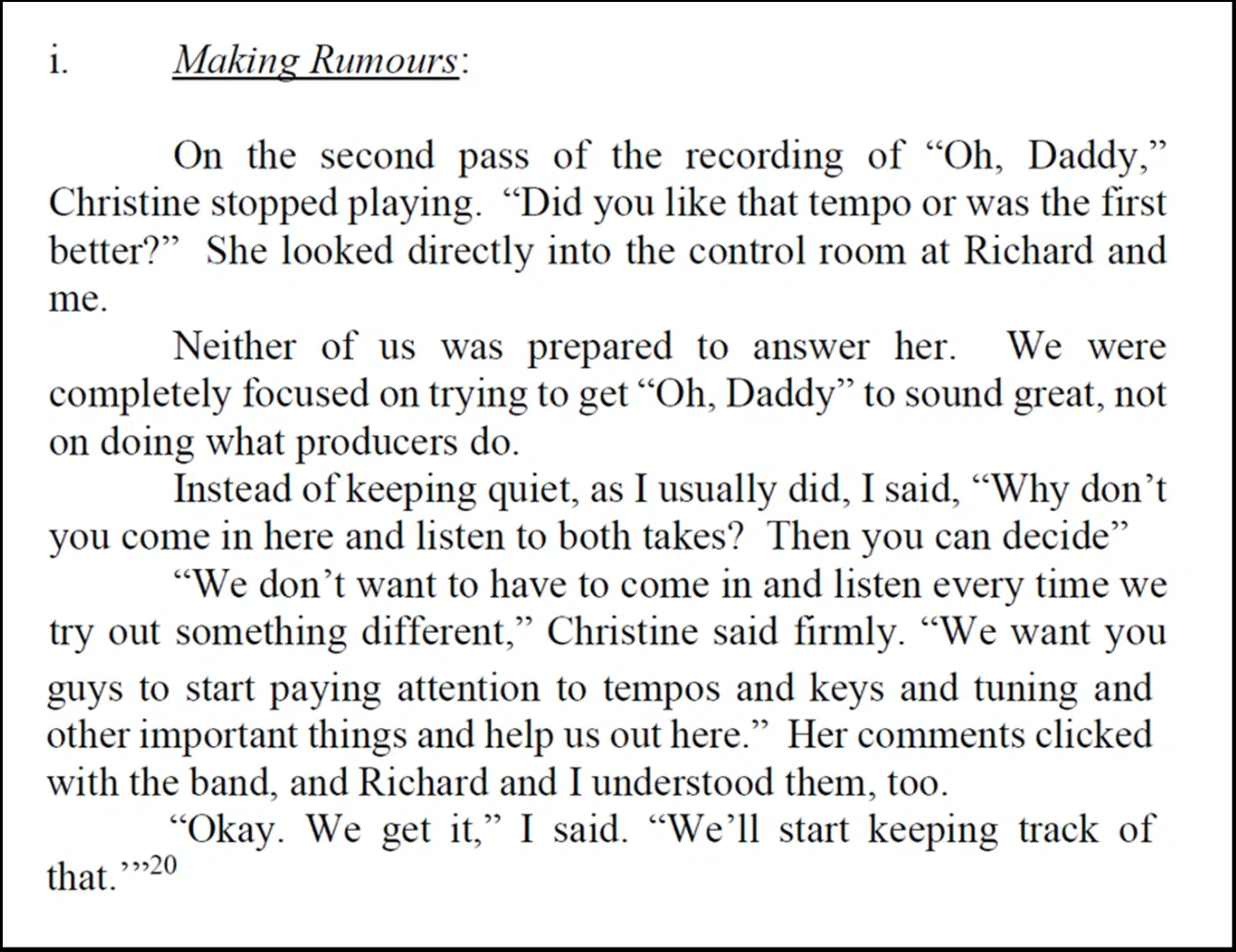

In addition, the plaintiffs point to dialogue that allegedly echoes exchanges in Making Rumours. For instance, they say the band’s debate over different takes of a song closely mirrors a specific conversation in the memoir, where Christine McVie asks Caillat and his co-producer to weigh in on various takes of “Oh, Daddy”:

Dreams of Copyright Protection

Facts Aren’t Protectable

Despite Adjmi’s recent press denials, the scenes described in the complaint do seem similar (though I haven’t read Making Rumours or seen Stereophonic). The problem for the plaintiffs, however, is that Making Rumours presents those scenes and dialogue as events that actually happened. Real-life events aren’t entitled to copyright protection—regardless of whether they’re salacious, were previously unknown, or took a lot of effort to uncover. As the Supreme Court has ruled, “Originality remains the sine qua non of copyright,” and true facts simply aren’t original creations.

This case differs from a previous legal battle involving Adjmi: a lawsuit over his Off-Broadway play 3C, loosely based on the TV sitcom Three’s Company. In that case, the court ruled in Adjmi’s favor because 3C was a parody of the sitcom and protected by fair use. But the plaintiffs in the Stereophonic case are suing over what they claim is the copying of real-life events, which makes proving copyright infringement much harder.

David Adjmi was previously sued over his Three’s Company parody 3C, but in 2015 the court found the play protected by fair use.

Case in point is the recent lawsuit over the magazine article that inspired the film Top Gun. As I discussed back in April, the court dismissed a copyright claim brought by the author’s heirs against Paramount Pictures on summary judgment. While acknowledging that the magazine article and Paramount’s film both featured the Top Gun flight school and described fighter pilots training and going on missions, the court ruled that because Top Gun is a real school, and the pilots discussed in the article were real individuals, those similarities weren’t protectable. Dialogue attributed to “real statements made by actual people” wasn’t protected either.

. . . Even if They’re Made Up

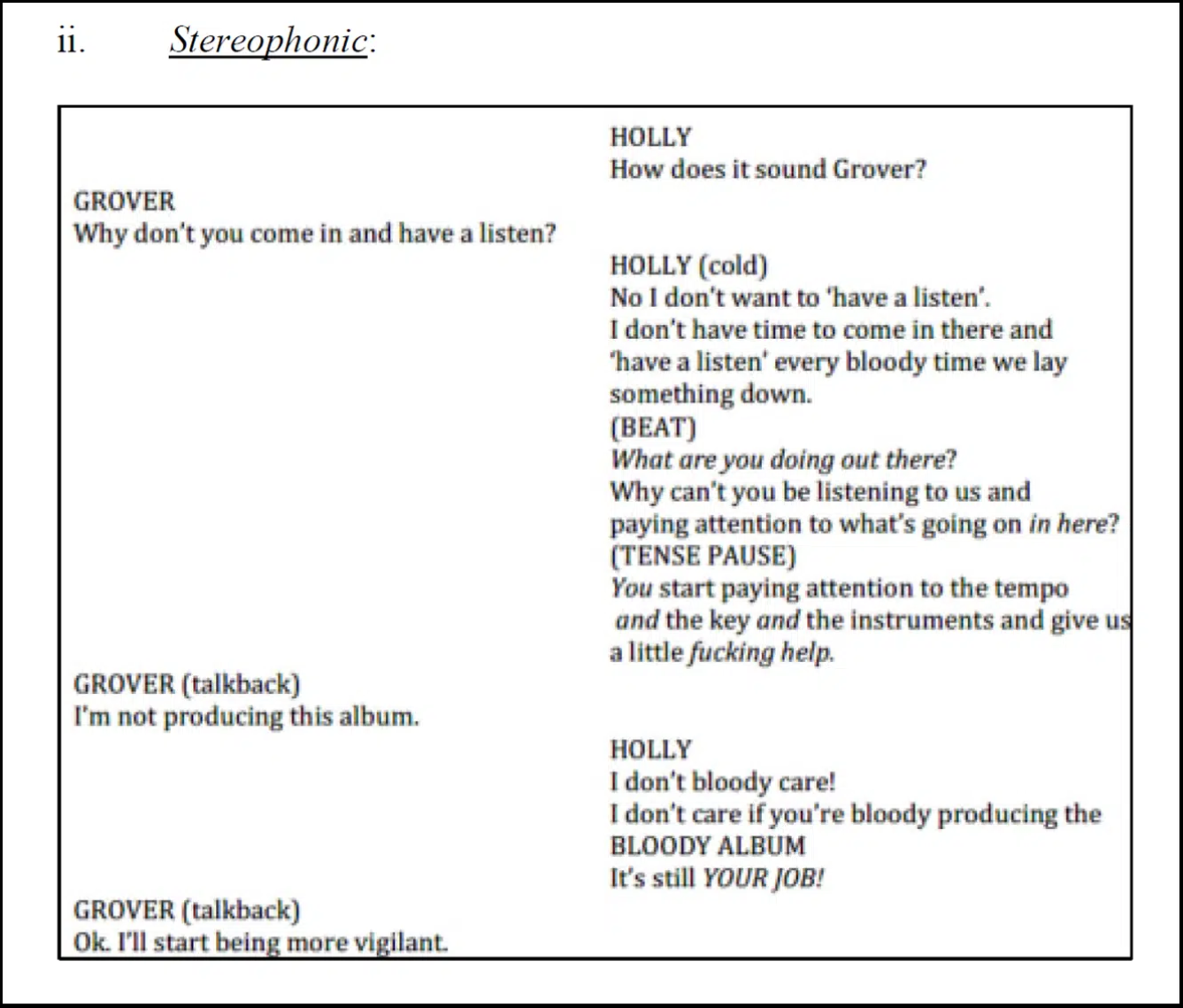

Another important limitation is the “asserted truths” doctrine, which I previously discussed in the context of the Jersey Boys lawsuit, Corbello v. Valli. In that case, the widow of Rex Woodard, co-author of Tommy DeVito’s autobiography, sued the creators of Jersey Boys, claiming they’d copied substantial portions of the unpublished book. The Ninth Circuit ultimately ruled in favor of the defendants, holding that even if Jersey Boys borrowed heavily from the book, the only elements copied were unprotectable facts.

The asserted truths doctrine says that if authors present events as fact, they can’t later claim copyright protection, even if it turns out that some of the content was embellished or fictionalized. Since DeVito’s autobiography purported to be an accurate account of the history of the Four Seasons, the court found that the similarities between the book and the musical weren’t infringing. This reasoning even extended to dialogue: “The dialogue is held out by the Work as a historically accurate depiction of a real conversation. The asserted facts do not become protectable by copyright even if, as [the plaintiff] now claims, all or part of the dialogue was made up.”

Corbello v. Valli: Facts Aren’t Copyrightable—Even if They’re Made Up.

Don’t Stop (Writing About Real People): The Legal Myth of Life Rights

Another principle that’s important to understanding the steep hurdles Caillat will face in his lawsuit is the widespread misconception about “life rights.” Hollywood studios frequently pay substantial sums for so-called “life story rights,” as Netflix did with Anna Sorokin for Inventing Anna. But here’s the truth: life rights are largely a legal fiction. While these deals may be standard entertainment industry practice, they’re more about avoiding headaches—like defamation or privacy claims—than securing any exclusive control over someone’s life story.

What studios are really paying for in life story deals is cooperation and an insurance policy. These contracts typically give producers access to interviews, personal materials, and behind-the-scenes stories, in addition to waivers for defamation and privacy claims. However, such agreements don’t confer any sort of monopoly over the life story itself. Anyone can make a movie, play, or television show about a real person or event so long as they’re careful to avoid defamation or implying any endorsement.

While Making Rumours offers a unique insider’s perspective on the creation of Rumours, the facts it describes—the who, what, where, and when of the band’s recording sessions—can’t be owned. The plaintiffs will have to prove that Stereophonic copied not just these facts, but their unique creative expression of those events. Complicating matters further, they’ll also have to distinguish their own original expression from the facts and dialogue they’ve presented as real events, which copyright law doesn’t protect.

Stereophonic

Second Hand News: Docudramas and the First Amendment

Another hurdle for the plaintiffs is the fact that Stereophonic, to the extent it portrays the story of Fleetwood Mac, would fall into the category of a docudrama—a genre that blends fact with fiction. Courts have consistently ruled that docudramas are protected by the First Amendment, which allows creators to embellish or fictionalize real-life elements for dramatic effect, provided that the work does not defame the people depicted or falsely imply their endorsement.

Rumours is one of the most well-known albums in music history, and the story of its creation has been extensively covered in hundreds of interviews, documentaries, and books. The producers of Stereophonic are constitutionally permitted to tap into that public fascination, with or without permission, and as long as the play steers clear of copying the original expression of Making Rumours, it will be protected.

Stereophonic

The Bottom Line

While the similarities between Making Rumours and Stereophonic may seem striking at first glance, copyright law doesn’t protect real events or factual accounts. For Caillat and Stiefel, the challenge will be proving that the play copied their unique expression of those events, rather than simply drawing from the same historical narrative. But once the actual characters, events and dialogue that Caillat claims were copied are stripped away from Stereophonic, the reality is that there’s just not much left for the plaintiffs to claim as original, protectable expression.

The bottom line is that while Ken Caillat and Steve Stiefel may have created a compelling memoir, showing that Stereophonic infringes their creative expression will be no small feat. The truth may be stranger than fiction, but in the world of copyright, it’s a whole lot less protectable.