Background

KCT GmbH & Co. KG (‘KCT’) filed for registration of EU trade mark no. 018906690 covering ‘vehicle windows for expedition vehicles’ in class 12.

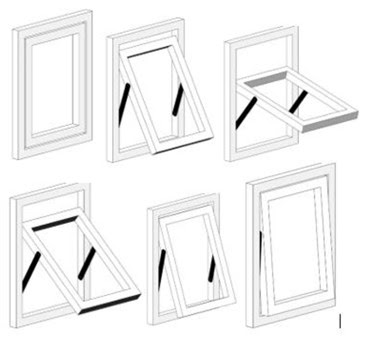

It was a motion mark, which showed the opening and closing of a window. The six second video clip is available here. The ‘storyboard’ looks like this:

The Board of Appeal’s decision

The BoA dismissed the appeal (R740/2024-2) holding that the application had to be rejected because it showed a functional process and lacked distinctiveness.

1. Functional sign (Art. 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR)

As regards the functional nature of the mark, the BoA referred to the purpose of Art. 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR, which is to prevent granting a monopoly on technical solutions or functional characteristics of the goods that consumers may seek in goods of competitors. In particular, it seeks to prevent the exclusive and permanent right, which a trade mark confers, from extending indefinitely the life of other rights (such as patents) that have limited periods of protection.

Although the wording of Art. 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR requires the goods to consist exclusively of characteristics necessary to obtain a technical result, minor arbitrary elements do not prevent this provision from applying as long as all essential characteristics have a technical function.

Since the trade mark in question was a motion mark and not a figurative mark, the individual pictures which the sign consisted of were deemed irrelevant. Instead, the movement in its entirety was decisive.

The BoA found that the opening and closing mechanism of the window was not a technical effect but the opening and closing as such had a technical function, namely to allow air into the vehicle. On that basis, the Board held that the trade mark showed nothing more than the opening and closing of a window. It contained no further arbitrary elements.

The black struts, which the applicant considered to be visible in an unusual way, were found to have a purely technical function because they were a supporting element that served to stabilize and reinforce the window.

The BoA rejected KCT’s argument that the movement of the window was unique. The conditions of Art. 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR do not have to be assessed on the basis of the perception of the relevant public or market conditions. Further, it could not be assumed that consumers had the technical knowledge to assess a technical feature of a product.

In accordance with consistent case law of the CJEU, the fact that alternative opening mechanisms for windows existed, which achieved the same technical function, was considered irrelevant.

For the sake of completeness, the Board referred to the Common Practice of the European Intellectual Property Network CP11 on “New Types of Marks: Examination of Formal Requirements and Grounds for Refusal”, which contained the following example of a motion mark showing the movement of a thermostat when increasing the temperature:

2. Lack of Distinctiveness (Art. 7(1)(b) EUTMR)

The BoA agreed with the EUIPO’s examiner that the motion mark lacked distinctiveness.

The Board found that it was generally known that manufacturers of technical goods published videos (e.g. on YouTube) to explain the functionality of their products or to promote the product’s technical features. The relevant consumer would perceive the motion sequence merely as a demonstration of the window’s functionality but not as a source indicator.

The BoA did not consider it to be decisive whether the functionality of the window or the window itself exhibited unique features because novelty or originality were no relevant criteria for assessing the distinctive character.

Comment

The decision highlights the stringent requirements for registering movement marks, particularly when they show movements with a technical effect. The ruling is consistent with previous decisions. For instance, a sequence showing the cutting of cheese was refused registration because it lacked distinctiveness (R314/2023-2; IPKat here).

The decision also shows that the absolute ground for refusal in the examiner’s rejection decision need not be the only one against which an applicant has to defend its application. The BoA has the same competence as the examiners at the EUIPO, meaning that it can raise additional absolute grounds for refusal on its own motion.

The decision raises an interesting question regarding the subject matter of protection of motion marks. In the assessment of the distinctive character of the sign, the BoA referred to the fact that manufacturers publish videos showing the function of the trade mark. But is this relevant? Arguably, it would be relevant if the video sequence as such was protected. However, a motion mark is defined in Art. 3(3)(h) EUTMIR as

a trade mark consisting of, or extending to, a movement or a change in the position of the elements of the mark.

This definition seems to suggest that it is not the video sequence but the motion itself that is protected. It means that the trade mark could be genuinely used without showing the video but by selling windows into which the motion is integrated. Therefore, it seems that the general custom of videos being published to show the function of goods might not be decisive in the determination of the distinctive character of a motion mark.