From the start of the modern Olympic Games, swimming has not only demonstrated athletic excellence but has also mirrored advancements in fashion and technology. Competitive swimwear has evolved significantly, embracing the latest performance-enhancing innovations.

Swimsuits

From the beginning of competitive swimming in the Olympics to the early 1990s, swimwear gradually moved in the direction of suits with less material, making movement in the water easier. Starting in 1992, companies like Speedo began developing drag-reducing fabrics, and consequently, swimmers began opting for greater coverage in swimsuits to increase drag-reduction as much as possible. This increased coverage continued though the early 2000s, when swimsuit manufacturers eventually produced full-body suits — until these suits were banned by the Olympics, and swimmers returned to wearing the greatest coverage suit in which they were allowed to compete.

Prior to the inclusion of swimming in the Olympics in 1896, swimwear, or “bathing costumes,” followed the fashion of the times, consisting of long dresses, stockings or bloomers, and shoes for women and one-piece knee-length wool rompers for men (Swimsuit Photos Now and Then: The Evolution of Bathing Suits | TIME). In the years prior to women’s Olympic swimming events, swimwear designs gradually shifted to offer less coverage and fewer layers. Men’s suits, however, remained largely unchanged during this period, with some color and style updates based on what was trending. When swimming was added to the Olympics, only men were allowed to swim, and they competed wearing the one-piece wool rompers, which became very heavy when wet.

Starting in 1912, women were allowed to swim at the Olympic Games in the 100-meter freestyle and the 4×100-meter freestyle relay (How Olympic Swimsuits Have Changed Over The Years (romper.com)). Men’s and women’s swimsuits were very similar by this time, consisting of a romper-style suit made from silk to reduce drag. However, the material became sheer when wet, leading to swimmers wearing underwear under swimsuits for added modesty (A Look Back at 116 Years of Olympic Swimsuits (yahoo.com)).

In 1924, suits designed specifically for women were released that included a built-in skirt to cover the hips (The Evolution Of Competitive Swimwear (swimswam.com)). The material was also changed to eliminate the problem of the suits becoming sheer when wet, although it was still made from silk (Sexism, Silk, and Shark Skin: Witness the Evolution of Olympic Swimwear | Teen Vogue).

Swimwear began trending towards modern-day swimwear in 1928, with the release of Speedo’s first racerback swimsuit (History of competitive swimwear | From racerbacks to supersuits (swimming.org)). This suit created some controversy due to its decreased coverage, which came to a head at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics when Claire Dennis wore the racer-back swimsuit, and many thought the suit was too revealing due to the low-cut back exposing her shoulders. The controversy almost prevented her from competing in all of her races (The Evolution Of Competitive Swimwear (swimswam.com)). At this time, male Olympians still preferred the classic tank-and-shorts style.

At the 1936 Berlin Olympics, men were allowed to compete bare-chested, after the release of a new swim short design for men (The Evolution Of Competitive Swimwear (swimswam.com)). This was the beginning of the trend towards the modern-day well-known version of the “Speedo” suit, a barely-there brief-style swimsuit bottom.

In the 1940s, the brief-style swimsuit gained popularity among men as suit styles trended towards less material for both men and women. At the 1948 London Olympics, the brief-style suits were popular among male Olympians (How Olympic Swimsuits Have Changed Over The Years (romper.com)), but women’s suits had not changed significantly from the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

In the 1950s, new materials were introduced in swimsuit manufacturing. Manufacturers began to include nylon in their suits, which provided a tighter fit and reduced drag in the water (How Olympic Swimsuits Have Changed Over The Years (romper.com)). In 1964, swimsuits became tighter and shorter (How Olympic Swimsuits Have Changed Over The Years (romper.com)), and were produced in a variety of colors.

Beginning in 1976, compression suits, known as “paper suits,” because of the papery feel of the swimsuits, were introduced. The compression suits were designed to fit exceptionally tight, thereby reducing drag and increasing speed (The Evolution Of Competitive Swimwear (swimswam.com)). At this time, manufacturers also began producing suits with detailed patterns, which became popular among swimmers.

Throughout the 1980s, swimsuits for women became higher cut in the leg and featured thinner straps. Manufacturers also started incorporating elastane into the nylon fabric to increase elasticity and allow for an even tighter fit (The Evolution Of Competitive Swimwear (swimswam.com)). These changes aimed for increased speed through better movement and decreased drag.

In the following years, technological advancements led to a speed race in swimsuit manufacturing, broken records, and controversy. Speedo released a new suit called the “S2000” in 1992, which promised a 15 percent reduction in water resistance (The competitive swimsuit and its evolution (schwimmschule-steiner.at)). This suit kicked off the rapid development of faster and faster swimsuits.

In 1996, Speedo released the “Aquablade” for the Atlanta Olympics. This new suit had increased coverage to help with speed and reducing drag, which marked the start of the trend towards competition swimsuits with more coverage (20 Years Of Speedo Fastskin (swimswam.com)). In 2000, Speedo released their most technologically advanced suit yet, modeled after sharkskin and incorporating compression and ridges in the fabric and construction (20 Years Of Speedo Fastskin (swimswam.com)). This suit led to the development of other similar products over the next four years, such as the “Powerskin” by Arena (The competitive swimsuit and its evolution (schwimmschule-steiner.at)).

Continuing the trend of full-body compression suits, Adidas launched JetConcept in 2003 (The competitive swimsuit and its evolution (schwimmschule-steiner.at)). In 2004, Arena launched an updated “Powerskin” suit called “Powerskin X-treme” and Speedo released the “Fastskin FSII,” both designed to reduce drag while maintaining range of movement (The competitive swimsuit and its evolution (schwimmschule-steiner.at)) (20 Years Of Speedo Fastskin (swimswam.com)).

The next major development in swimsuit technology came in 2008, with the release of Speedo’s patented “LZR Racer” swimsuit. This new swimsuit incorporated the non-textile material polyurethane into the nylon and elastane fabric and had ultrasonically welded seams. The patented swimsuit was structurally designed to compress a swimmer’s body and thereby improve performance by reducing surface and form drag and improve buoyancy and stability in the water (U.S. Patent No. 8286262). It features a base layer that covers the swimmer’s torso and legs and additional panels that are laminated on the outer surface of the base layer (U.S. Patent No. 8286262). This suit extraordinarily reduced drag in the water and lead to significant controversy as the suit was compared to “technical doping” (SetMaker – The Evolution of Swimwear: A Look at the History and Advancements in Competitive Swim Gear).

In 2009, the first swimsuits made entirely of non-textile materials were released. These suits were largely worn at the 2009 World Championships, where 43 world records were broken, primarily attributed to the new swimsuits (Study: New Swimsuit Aided Record-Setters at 2009 Championships | WIRED).

As a result, the International Swimming Federation (FINA) banned all non-textile materials and full-body swimsuits. FINA also put forth regulations as to how much coverage is allowed for both men’s and women’s swimsuits (The competitive swimsuit and its evolution (schwimmschule-steiner.at)). These regulations, while limiting, have not yet entirely prevented technological developments to competition swimsuits.

In 2020, Arena released the “Carbon” suit, utilizing carbon fiber and elastane to better balance compression and flexibility (SetMaker – The Evolution of Swimwear: A Look at the History and Advancements in Competitive Swim Gear). TYR’s swimsuit patented in 2022 features an intricate network of tension bands disposed interior [MJA1] to the external surface of the swimsuit and a plurality of reinforcement liners as well as strategically positioned ridges and drains to prevent water intrusion from being retained within the suit components (U.S. Patent No.11,246,357). TYR patented another swimsuit in 2023, featuring a seamless back and a network of tension bands to optimize motion, posture, and water flow over and off the swimsuit (U.S. Patent No. 11,751,610).

Undeterred by the ban on its record-breaking “LZR Racer” swimsuit, Speedo has continued to seek ways to engineer swimsuits that help swimmers move faster. Speedo’s latest breakthrough.the “Fastskin LZR,”is its most water repellent suit yet, thanks to patented water repellency technology developed by Lamoral, a company that developed coatings for protecting satellites from corrosion in space (https://lamoral-coatings.com/news/lamoral-and-speedo-announce-collaboration). The “Fastskin LZR” suit was approved by World Aquatics and was worn by Team USA swimmers vying for gold at the Paris Olympics (https://lamoral-coatings.com/news/lamoral-and-speedo-announce-collaboration).

Caps and Goggles

Swimsuits are not the only gear considered essential by competitive swimmers. Bathing caps have been used for centuries to protect the wearer’s hair, but in the 1920s, the invention of latex allowed for the creation of tighter fitting and more stretchy bathing caps, leading to the swim caps popular today (History of Swim Caps | Epic Sports). The use and development of swim caps tapered off during World War II, as the materials used for swim caps were needed for the war effort.

In the 1980s and 90s, the production of swim caps for competition greatly increased, as there was a renewed interest in the sport of swimming (History of Swim Caps | Epic Sports). Today, swim caps are still popular among competitive swimmers and are made from materials like latex and silicon, available in many styles and colors.

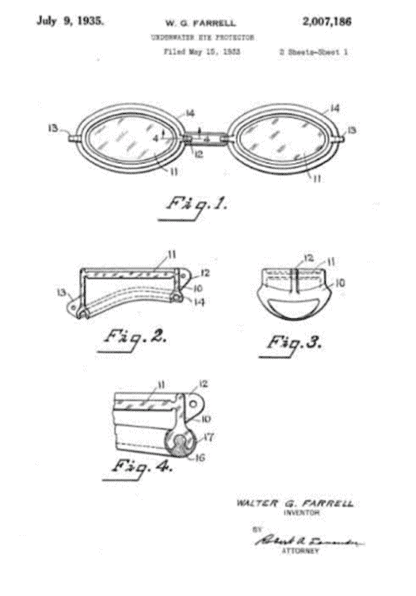

Goggles are the other piece of equipment considered essential by most competitive swimmers. The first-ever produced goggles did not have lenses and were therefore minimally effective in protecting the wearer’s eyes from the water. Over the years, swimmers began using motorcycle goggles to provide more protection, and worked to waterproof them. In 1935, Walter G. Farrell patented a goggle design called “Underwater eye protector” (Swim Goggles: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know (yourswimlog.com)). Eventually, mass production of goggles began around the 1970s.

By 1972, most swimmers were using goggles in practice, and some were starting to use them in competition. At this time, advancements were being made to reduce fog and add UV protection (The history of swimming goggles | LoneSwimmer). In 1976, goggles were approved to be used by swimmers in the Olympics (When Were Swimming Goggles Invented? History of Swim Goggles – Optics Mag). In the 1990s, goggles became accepted across the sport and further advancements were made in comfort, UV protection, and anti-fog technology.

The next major advancement in goggle technology was in 2017, when TheMagic5 created a new 3D-printed goggle design customizable for each swimmer to provide optimal fit (The Evolution of Swimming Goggles: A Timeline (themagic5.com)). Advancements in sports technology have largely led to the integration of smart sensors in sports gear. In 2019, Form released a set of smart swim goggles that provide training stats on a heads-up display (Form Swim Goggles are bringing augmented reality into the water – Wareable).

The technological advancements made to swimwear and gear and the changing styles have allowed for enhanced competition and displays of personal style through swimsuits, caps, and goggles.

A special thanks to Emma Leider for her contributions to this article.

[View source.]