In light of the recent UTIDELONE patent grant order by the Indian Patent Office, Bharathwaj Ramakrishnan analyses the tactic to present a pharmaceutical invention as a composition to overcome Section 3(d) scrutiny and how this could be bad in law. Bharathwaj is a 3rd year LLB Student at RGSOIPL, IIT Kharagpur, and loves books and IP. His previous posts can be accessed here.

Formulation/Composition Claims and Section 3(d): Analyzing the Uitdelone Pre-grant Opposition Order

By Bharathwaj Ramakrishnan

“Name of the game is the claim.”

– Giles Rich, the former Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit

Recently, the Patent Office issued an order for the grant of a patent titled “SOLID ORAL FORMULATION OF UTIDELONE” (202337012007) (pdf, also see this LinkedIn post by Sandeep Rathod here). The application had faced a pre-grant opposition from the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance who had objected on multiple grounds. Even though I will briefly discuss the entire Order, I will be focusing on two specific lines stated in the Order in relation to Section 3(d) :

“Present set of claims 1 to 7 relate to a solid oral formulation comprising Utidelone and pharmaceutically acceptable excipients. Said composition is not known in the prior arts”. (page 20-21 of the order)

With this observation, the Patent Office concluded that the claims do not attract the application of Section 3(d) (commonly known for being against ‘evergreening’, see Prof. Basheer’s paper, which provides a great primer on the Section and its importance). In this post, I will argue that the observation by the Patent Office with regard to Section 3(d) is premised on the pronouncement made by the IPAB in Ajantha Pharma Limited Vs. Allergan Inc (discussed in blog here) in the context of combination drugs which is bad in law (more on this later) and might not even be relevant to the present case. Lastly, I will also argue that this observation by IPAB on Section 3(d) has allowed applicants to escape scrutiny under Section 3(d) through clever claim drafting. Before we go to the meat of the issue, we will see the claims and the order in brief.

The Order and Patent Claims in Brief:

The Patent application in issue is titled “SOLID ORAL FORMULATION OF UTIDELONE”. The application seeks to patent a solid oral formulation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient Utidelone. Utidelone, the active ingredient in the composition, has anti-cancer properties and has shown potential for treating different types of cancers (page 8 of complete spec, also see here). The independent claim of the application (which also tends to be the first, and always has the broadest scope in a Patent claims set) is as follows:

A brief description of the claim is provided below:

- It is a solid oral formulation with Utidelone as an active ingredient + excipients (excipients are substances other than the active ingredient that would be in a final pharmaceutical product, see here)

- Then claim provides for the nature of the formulation/composition ( micropellet or tablet)

- It provides for the various types of excipients that would be used in the formulation/composition.

- It provides for a ratio of active ingredient: excipient

- It provides some info on the physical properties of the active ingredient (amorphous or molecular form)

- Later, the dependent claims provide details as to from which substances the excipients would be selected and specific ratios at different formulations as claimed in claim 1.

Now, with the independent claim explained, it has to be made clear that it is a formulation/composition claim. This understanding acquires significance later down the post and has to be contrasted with a combination claim which is directed towards a combination drug with two or more active ingredients – see here. The Guidelines For Examination Of Patent Applications In The Field Of Pharmaceuticals 2014 (see here) state that formulation/composition is a specific type of product claim.

One can now move on to the Order. As was stated earlier, the opponent challenged the application on various grounds and was unsuccessful. The Patent Office concluded that the claims were novel, had inventive steps, and were not barred by either Section 3(d) or (e). The Order also noted how the solid oral formulation being claimed has improved drug release and increased bioavailability, hence exhibiting technical advance over the prior arts and was non-obvious over the prior arts. Also, the Patent Office concluded that the formulation/composition that the Applicant was claiming was not a known substance; hence, Section 3(d) does not apply. Finally, the Order stated that the composition was not a mere admixture and had a synergistic effect, and thus, the opposition failed, and the patent was granted.

Is Solid Oral Formulation of Utidelone a “Known Substance”?

It is clear from the order and the complete specification that Utidelone, the active ingredient, has been disclosed in the prior art. In other words, Utidelone is a “known substance” from the prior art. But the Applicant had asserted that a solid oral formulation, as claimed in claim 1 is a new formulation/composition containing Utidelone and is not a “known substance” under Section 3(d) and hence Section does not apply, and the Patent Office agreed.

Now, to understand why the Office accepted the argument made by the Applicant, one has to look into the written submissions provided by the Applicant during the opposition proceedings. In the written submission, the applicant lays out the argument that the solid oral formulation of Utidelone, as revealed in claim 1, is not a known substance. To buttress their point, they cite the case of Ajantha Pharma Limited Vs. Allergan Inc (IPAB 2013) (page 52, Author wishes to note here that in the written submissions, it stated as Allergan Inc Vs Allergan India, which might be due to a typographic error as the para quoted in the written submission is from Ajantha Pharma), which made an observation on the question of whether a combination drug having the active ingredients Brimonidine and Timolol plus a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier would fall under the scrutiny of Section 3(d).

The IPAB ruled it does not and stated that the term “combination” in Section 3(d) could only mean a combination of derivatives listed in the explanation clause or a combination of the derivatives with the known substance and hence the claims in the suit Patent would not come under the scrutiny of Section 3(d) (para 83).

Now, it also raises one question as to how the observation made by IPAB in a case involving a combination claim is being cited in a case involving a formulation/composition claim to argue that Section 3(d) does not apply.

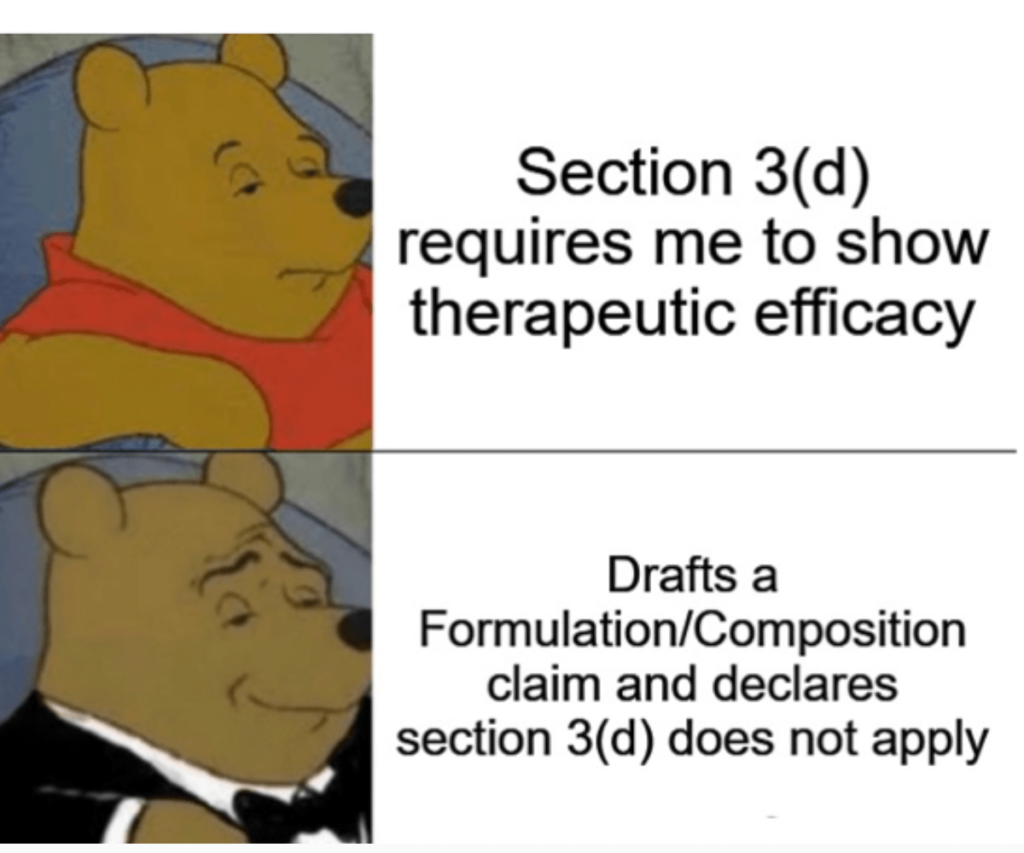

Evading Section 3(d) Scrutiny through Clever Drafting:

In their 2018 AccessIBSA paper (see here), the authors attempted to empirically figure out how the anti-evergreening provisions (Sections 3(d), (e) and (i)) have been implemented by the Patent Office. The analysis period is from 1995 to 2016, and it includes collecting all the available data related to pharmaceutical patents. The authors analyzed the prosecution history of 50 applications post-Novartis to analyze the prosecution strategies employed by the applicants to deal with Section 3(d). As the report puts it “A common strategy has been to draft a formulation/composition/combination claim to move the application away from the scrutiny of Section 3(d)”. The paper notes that the applicant also in some cases cites Ajantha to make a case that Section 3(d) does not apply (similar to the current case). Thus, this observation made by Ajantha in the context of combination claims has lent support to the applicant’s attempt to move away from Section 3(d) scrutiny (but this strategy might also fail, such as the high-profile Bedaquiline case) I argue that there are two major issues with relying on the ratio held in Ajantha with regards to Section 3(d). First, the issue of citing Ajantha in a case involving a formulation/composition claim when the suit patent in question in Ajantha had a combination claim; and secondly, regardless, Ajantha should be seen as bad in law.

| Section 3(d) : the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance that does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance or the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant. Explanation.—For the purposes of this clause, salts, esters, ethers, polymorphs, metabolites, pure form, particle size, isomers, mixtures of isomers, complexes, combinations and other derivatives of known substance shall be considered to be the same substance, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy; |

Adarsh Ramanujan in his wonderful book (see here (page 718-19), also notes that his new book on patent law has been released recently see here) has argued how Ajantha is bad in law. After referring to the observation made by the IPAB in Ajantha with regards to the word combination being related to the derivatives in the explanation he states, “The erstwhile IPAB has effectively added the word ‘thereof’ between combinations and other derivatives”. Thus, he concludes that the IPAB has, through interpretation, added words to the legislation without articulating reasons why such an addition is needed. It has to be noted here that the erstwhile IPAB cannot engage in creative interpretation when such interpretation is akin to a legislative amendment. He also proceeds to argue that ‘combination’ has a recognized meaning in pharmaceuticals which means fixed-dose combination (FDC) or drugs with two or more active ingredients and hence the interpretation by Ajantha which excludes the FDC from Section 3(d) and restricting it to the derivatives in the explanation clause is against the specific policy goal that Section 3(d) seeks to advance which is prevention of evergreening.

Thus IPAB through Ajantha has unwittingly allowed applicants to use the case to evade scrutiny under Section 3(d). Likewise, it has been argued elsewhere that the narrow reading of the combination has allowed applicants to bypass the Section both in the case of combination and composition claims (see the paper cited above).

Thus we come to the second issue with regard to citing the observation made by Ajantha with regard to interpreting the word “combination” in Section 3(d) in a case involving a formulation/composition claim. Adarsh Ramanujan notes (here page 719) how the word “Other derivatives” could be interpreted by applying the principle of ejusdem generis (see here for more on that principle) and concludes that the definition of the term must be limited to only those derivatives that would result in the same “known substance” being activated upon consumption. Likewise, this interpretation would also advance the specific policy goal Section 3(d) seeks to achieve. Thus, based on this understanding of the phrase “Other derivatives“, it is reasonable to claim that any formulation/composition claim with an active ingredient that has been revealed in the prior art (as in this case) would fall under the definition of “Other derivatives” and hence the observation made by Ajantha in this regard even if assumed to be accurate would be irrelevant as the observation made in Ajantha was limited to the word “combination” and not “other derivatives“.

Would the Present Application Survive the Scrutiny under Section 3(d)?

Now that I have made a case for combination/formulation claims where the active ingredient is revealed in prior art must pass the check under Section 3(d) and that it would fall under “other derivatives” of the “known substance” one wonders whether the current invention would have survived scrutiny under Section 3(d)?

From the order, it is easy to gather that the active ingredient Utidelone is revealed in the prior art (see page 17 of the order). If Utidelone is a “known substance” with a “known efficacy” (anti-cancer properties, it has to be noted here that Novartis vs Union of India 2013, hereinafter Novartis, was clear that “known” efficacy doesn’t mean it has to be conclusively proved para 158-59) it is obvious that the solid oral formulation of Utidelone + excipients must show enhanced therapeutic efficacy over the known substance (see Novartis para 180). In the order, it is clear that the new composition/formulation has increased bioavailability and improved drug release. But it is clear from reading Novartis (para 180) that therapeutic efficacy must be interpreted strictly. Secondly, increased bioavailability does not automatically lead to increased therapeutic efficacy (Novartis para 187-89). Thus increased bioavailability in of itself is not enough to clear Section 3(d) and likewise, the fact that the court has stated that the efficacy must be interpreted strictly, hence improved drug release might not in itself be sufficient and show that the new form has enhanced efficacy. Thus one can argue if the Patent Office had concluded that Section 3(d) is applicable in the present case and scrutinised the application under the Novartis standard the applicant must have had to establish an additional tier of fact and make the connection on how increased bioavailability and improved drug release leads to therapeutic efficacy. Thus it is clear that the current evidence submitted and accepted by the Office with regard to bioavailability and improved drug release might not be sufficient to clear the 3(d) bar.

The author wishes to thank Swaraj for his valuable input.